Everyone knows someone that has a wobbly knee gait. The knees seem to touch and dive inward while the feet splay outward. This looks especially awkward during running and runners may complain of scuffing their knees or scuffing the inner part of their calves (due to the rotation). Some individuals are indeed born with their hips in this manner (also called femoral anteversion) and will naturally stand with their feet turned in due to their hip structure. Most people are either weak or have poor movement patterns. Today we are going to talk about why this might be happening, the implications and what to do about it.

Image from www.sporting-heroes.net

The classic Priscah Jeptoo. Granted she is very fast, but that is a clear femoral internal rotation deficit (combined with knee valgus). This is an example that people can still running very fast with these deficits, but you cannot beat biomechanics and tissue physiology.

RUNNING MOVEMENT IMPAIRMENT

Hip Internal Rotation refers to the inward rotation of the thigh toward the center of the body. It is a normal motion and about 45 degrees of passive rotation is considered normal (not during gait). Excessive and uncontrolled hip internal rotation is NOT normal. During the running gait this commonly occurs during the loading and stance phases of gait as part of normal shock absorption. This may be seen with pelvic drop and/or hip adduction, further putting the knee in a valgus (knock knee) position. This can place excessive pressure on both the knee and hip joint. This is also a common pathology seen in those with femoral acetabular impingement (Loudon & Reiman, 2014)

ASSOCIATED INJURIES

Common injuries associated with an excessive femoral or hip internal rotation deficit include patellofemoral pain, iliotibial band syndrome and trochanteric bursitis (Powers, 2010). The first two listed also happen to be the top two most common injuries experienced by runners (Taunton et al., 2002). There are more of course, but we will stick to the top ones.

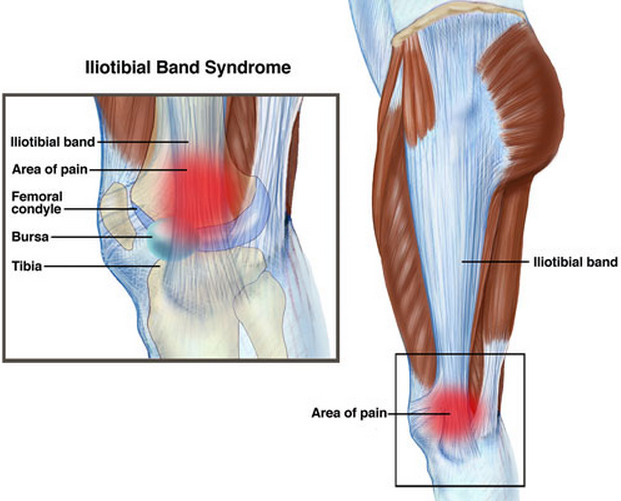

Image from Ortho Bullets

The association with patellofemoral pain comes from an issues with tracking of the patella. As the femur rotates inward, the patella/knee cap usually does not follow. Thus your train (patella) is not lined up with the tracks (distal femur). This can lead to some grinding in that area, irritation and more as you load that up with higher activity or running mileage. For those that have some grinding or crepitis, this may be the source. It is important to note that crepitis can be NORMAL (ie normal wear and tear) and if it occurs without pain, it is not something to worry about.

Image from The Gait Guys

The contribution of femoral internal rotation to iliotibial band syndrome comes from both strain on the iliotibial band as well as overuse of the muscles that attach onto this structure. An example of this is the tensor fascia latae, which unfortunately is a internal rotator of the hip and may further contribute to this issue. The TFL, a poor abductor of the hip, is usually compensating for the associated knee valgus or hip adduction component, usually coming from a weak glute medius and/or maximus. Those muscles should be your primary abductors and stabilizers of the pelvis, but when an individual is not using them, the TFL kicks in to save the day, albeit poorly. The iliotibial band is a wonderful structure that provides lateral stability to the knee and hip. It is a passive structure (so stop foam rolling, cupping, massaging it. Treat the source not the symptoms) that is an extension of the glute max and the tensor fascia latae. So as that knee rotates in, that poor iliotibial band is getting yanked on as it tries to help you keep that knee lined up (and stable) to appropriately attenuate the shock of landing. The quadriceps and glute muscles are your primary shock absorbers during gait. If everything isn't lined up properly, the muscles will not be effective in properly activating to attenuate that impact.

Image from Ortho Bullets.

The upper part of what is labeled the IT band is actually a

combination of the muscular components of the tensor fascia latae and glute max.

The trochanteric bursitis or lateral hip pain will usually occur for the same reason as the ilitioband syndrome above. This is due to the fact that this bursa sits underneath the proximal aspect of the iliotibial band. So if the hip is rotating in uncontrolled and putting stress on the iliotibial band, excessive shearing may occur at the trochanteric bursa. Which over time may irritate it, cause some inflammatory processes to start due to possible tissue damage and there you have trochanteric bursitis.

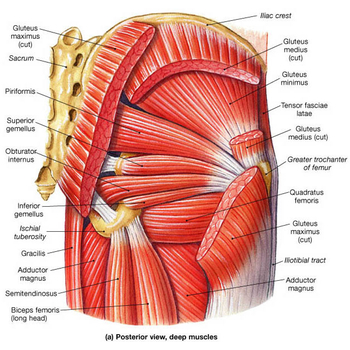

Image from Physiopedia.

The many deep hip external rotators in the center with the

glute max and other hip muscles.

CORRECTIONS

Femoral or hip internal rotation is controlled by the deep hip external rotators and the gluteal muscles, particularly the glute max. These should be one of the primary focuses of any rehab or training program to control the above running movement impairment. Classic and common exercises given for this deficit include the clamshell, monster walks, squats with therabands and more.

Clamshell exercise. Make sure you are only moving from your hip.

Common compensations include rotation from the trunk.

Add bands or a side plank to this to challenge yourself.

Add bands or a side plank to this to challenge yourself.

Many of the above are great foundational exercises for strength or activation. I do NOT want to disregard or downplay these exercises as they are great for building and activating muscles in isolation or in a somewhat functional pattern. I'll be honest that I do not give the clamshell to my patient anymore as I would rather give something harder like a side plank WHILE doing the clam to get some additional core stability going. It should be known that strength changes do not usually translate over to movement and motor control changes (Willy & Davis, 2011). Those come with practicing the actual movement. So if you do not have the strength to perform movement, you need to practice the above. Load those clam exercises and hip rotator muscles up. As soon as you have that basic strength, move on to the movement.

Beginning position for the Single Leg Squat

Start lined up, finish lined up. Put your hands on your pelvis to

make sure your hips don't drop either.

This is why my favorite exercise for this is the single leg squat. It is very similar to running, as running is a series of one leg squats/hops. It also happens to be a great screening tool for injury risk (Ugalde et al 2015) because it is such a similar activity to many athletic movements. Like any exercise, there is way to do them well and a way to do them poorly. Another reason for it being a great screening tool: if you look terrible doing a single leg squat, you may look terrible performing your activity!

Keep the knee lined up over your toes.

Drop your hips down into a squat position while keeping this alignment.

Start with mini squats and progress lower as

you get stronger and gain more control.

A mirror works very well for this situation. Stand in front of one and watch what your knee does as you squat. If you see it fall inwards, focus on keeping it over your toes. Do NOT overcompensate and pull it outside of your toes. That is an over correction and creates other sets of issues (also another great way to irritate the iliotibial band). Do it correctly. If you really need help, attach a band to something and have it pull inward to give your body the extra cue to pull the knee back to the center.

Use a band as an additional cue if you are having trouble keeping that knee straight.

You may feel your hip muscles start to burn. Congrats, you are not only building a better movement pattern but you are strengthening your hip (and lower leg muscles) in a functional manner. This is not an exercise you will usually do 3 sets of 10 reps. This is an exercise you do higher reps of to practice and create a new movement pattern. Building up to 30-50 reps if you are a distance runner or aerobic athlete or 8-12 sets with higher weight if you are a sprinter or anaerobic athlete. Optimally you will have a mix of both. Practice the high reps after your training and hit the high weight during your gym days. Both strength and motor control are important.

The Single Leg Fire Hydrant. Good for glute activation on both sides.

A favorite of mine. Also great for knee alignment.

Combine the fire hydrant exercise with a single leg squat

Once you have mastered this and can maintain these mechanics without thinking, you should progress that function even further. Single leg hops are the next step (pun intended). Start in place, then forward hops and if you want to get fancy, lateral hops are a really good way to challenge this new skill of yours. The focus should be on your mechanics. Since this a higher load plyometric exercise, dosages of 3-5 sets x 6-8 reps should be utilized initially then slowly increased. Finally, you should include this into your running. Running on a treadmill with a mirror in front is a great way to get some feedback on this and see what your are naturally doing. As you figure it out, gently correct it and practice this the same way you do intervals! This will take time and practice. The strength building, motor pattern changing and movement improvement can take upwards of 6-8 months (if not more) to really cement. Strength improvements take at least 8-12 weeks to be truly implemented (the short term gains you usually see are more neuromuscular). So add that on top of learning the movement and have some patience. It is WORTH it to get back to running pain free or potentially decrease your injury risk.

Single Leg Hops. Landing is the most important part. Your knee should stay

stable over your toes. It should not travel inside OR outside the line of your toes.

Both directions indicate a lack of control.

It should be clear that the goal here is not to stop internal rotation of the hip. It is a very important motion that everyone should have especially to get into the terminal stance phase of gait. However, it does need to be controlled via muscle eccentric strength and motor control. This may improve your ability to shock absorb, run faster, farther and more. That previous statement is not necessarily supported by research. However the above impairment is indeed linked to several injuries. So I will leave it up to you whether you want to take care of it or not. Personally, as someone who wants to run as long as possible, I believe it behooves all of us to work on all the important little things to keep us healthy. You should be able to move in all directions and want to emphasize you need mobility. However the mobility needs to be controlled. The better alignment you can maintain through motion, the better you will move.

A sneak peak from the next running impairment post.

Thanks for reading!

Matthew Klein PT DPT OCS

Doctor of Physical Therapy

Board Certified Orthopedic Clinical Specialist

Kaiser SoCal Manual Therapy and Sport Fellow

Doctor of Physical Therapy

Board Certified Orthopedic Clinical Specialist

Kaiser SoCal Manual Therapy and Sport Fellow

***Disclaimer: As always, my views are my own. My website should not and does not serve as a replacement for seeking professional medical care. I have not evaluated you in person, am not aware of your injury history and personal biomechanics, thus am not responsible for any injury that you may incur from the performance of the above. I have not prescribed any of the above exercises to you and thus again am not responsible for any injury that may occur from the performance of the above. This website is meant for educational purposes only. If you are currently injured or concerned about an injury, please see your local physical therapist. However, if you are in the LA area, I am currently taking clients for running evaluations.

REFERENCES

1. Cant, J., Pineux, C., Pitance, L., Feipel, V. (2014). Hip Muscle Strength and Endurance in Females with Patellofemoral Pain: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis

2. Loudon, J. & Reiman, M. (2014). Conservative management of femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) in the long distance runner. Physical Therapy in Sport, 15. doi: 10.1016/j.ptsp.2014.02.004

3. Powers, C. (2010). The Influence of Abnormal Hip Mechanics on Knee Knee Injury: A Biomechanical Perspective. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 40(2). doi: 10.2519/jospt.2010.3337

4. Taunton, J., Ryan, M., Clement, D., McKenzie, D., Lloyd-Smith, D., Zumbo, B. (2002). A retrospective case-control analysis of 2002 running injuries. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 36(2). doi: 10.1136/bjsm.36.2.95

5. Ugalde, V., Brockman., C., Bailowitz, Z.,Pollard C. (2015). Single Leg Squat Test and Its Relationship to Dynamic Knee Valgus and Injury Risk Screening. Physical Medicine & Rehab; 7(3): 229-235. doi:10.10.16/j.pmrj.2014.08.361

6. Willy, R., Davis, I. (2011). The Effect of a Hip-Strengthening Program on Mechanics During Running and During a Single-Leg Squat. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 41(9). doi: 10.2519/jospt.2011.3470

REFERENCES

1. Cant, J., Pineux, C., Pitance, L., Feipel, V. (2014). Hip Muscle Strength and Endurance in Females with Patellofemoral Pain: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis

2. Loudon, J. & Reiman, M. (2014). Conservative management of femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) in the long distance runner. Physical Therapy in Sport, 15. doi: 10.1016/j.ptsp.2014.02.004

3. Powers, C. (2010). The Influence of Abnormal Hip Mechanics on Knee Knee Injury: A Biomechanical Perspective. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 40(2). doi: 10.2519/jospt.2010.3337

4. Taunton, J., Ryan, M., Clement, D., McKenzie, D., Lloyd-Smith, D., Zumbo, B. (2002). A retrospective case-control analysis of 2002 running injuries. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 36(2). doi: 10.1136/bjsm.36.2.95

5. Ugalde, V., Brockman., C., Bailowitz, Z.,Pollard C. (2015). Single Leg Squat Test and Its Relationship to Dynamic Knee Valgus and Injury Risk Screening. Physical Medicine & Rehab; 7(3): 229-235. doi:10.10.16/j.pmrj.2014.08.361

6. Willy, R., Davis, I. (2011). The Effect of a Hip-Strengthening Program on Mechanics During Running and During a Single-Leg Squat. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 41(9). doi: 10.2519/jospt.2011.3470

Like and Follow Doctors of Running

Facebook: Doctors of Running Twitter: @kleinruns

Instagram: @doctorsofrunning Direct Contact: doctorsofrunning@gmail.com

Please feel free to reach out, comment and ask questions!